The ‘Desecration of Sacred Nature for Human Beings’ – Reimagining Kafka’s in State of the Ape Address

(All images are property of Mewzi Arts).

Last Christmas, I volunteered at Theatre Arts, a small theatre near the foot of Devil’s Peak Mountain in the Observatory suburb of Cape Town. Reanimating the soft-grey stone walls of an old church, the theatre claims its identity in its iconic blue door and its commitment to supporting independent artists.

While I was lucky enough to earn a complimentary ticket to an improvised alternative dance piece with local musicians, it was Mewzi Arts’ State of the Ape Address that I was particularly eager to see, a one-act show adapted from Franz Kafka’s (1917) short story A Report to an Academy. A Malawian theatre company based in Madsoc Theatre in Lilongwe, Mewzi Arts were in South Africa as part of their two-year tour, having premiered in Lilongwe’s Madsoc Theatre in 2023 and since performed in Tanzania, Kenya, and Mozambique.

A Report to an Academy is one of Kafka’s lesser-known works. The Austrian-Czech author is most famed for his surreal fiction The Metamorphosis (1915), in which a travelling salesman, Gregor Samsa, wakes up in terror to find he has turned into a human-sized bug. The Metamorphosis itself has inspired multiple theatrical adaptations, including Berkoff’s 1969 version. As with The Trial (1925), The Castle (1926), and other of his works, Kafka is preoccupied with dehumanisation, anxiety, and societal control and corruption.

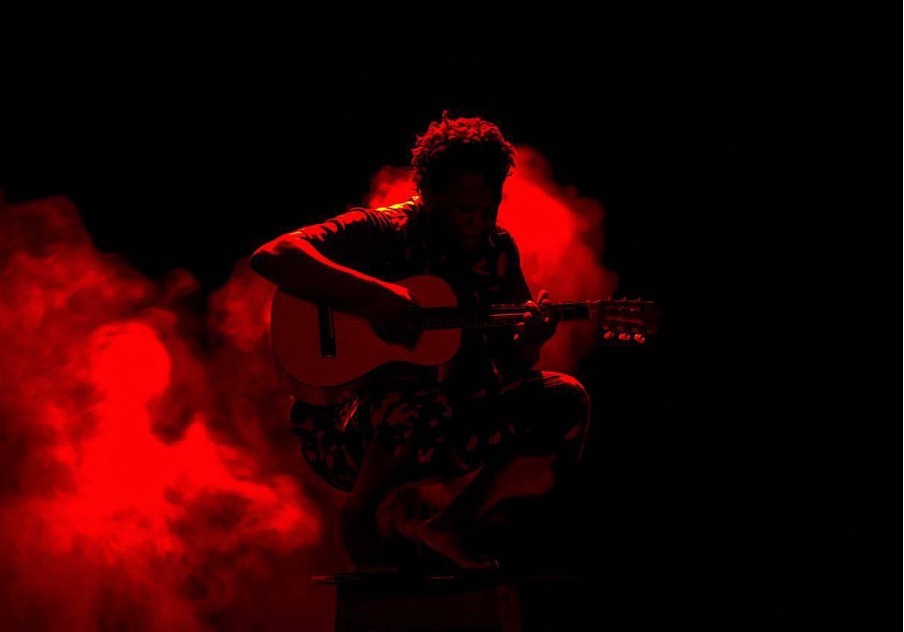

Clad in a ripped military vest and a frayed striped tie, Tawonga Taddja Nkonjera staggered onto the stage as Red Peter, an ape who is shot, captured, and caged on a boat to Europe. Asea, he learns to mimic human behaviour through spitting, talking, and drinking, dubbed by the sailors a talking ape, and eventually a human himself. In light of his transfiguration, Red Peter is deemed by his captors to be satisfactorily civilised to be integrated into human society.

In his ‘report’, Red Peter sets out to satisfy the Academy’s scientific curiosity on his development from animal to ‘man’, re-enacting for the audience the events of his humanisation. That same taste that Orwell’s Animal Farm gives you lingers in the breath of State of the Ape Address. While the message is different, Red Peter’s gradual transformation from ‘animal’ to human mimic employs similarly discomforting imagery to foreground the corrupt hierarchies of being through which society finds value and voyeuristically objectifies the ‘other’.

They don't want to understand, they just want to solve the riddle of my being. – State of the Ape Address

I had the pleasure of interviewing director Stanley Mambo and actor Tawonga Taddja Nkonjera on their insights into the play’s meaning, why it was relevant to contemporary audiences in South Africa and beyond, and its opportunity for physical theatre. A didactic text, A Report to an Academy, and Mewzi Arts’ adaptation, State of the Ape Address, blatantly grapple with universal themes of ‘the misconception of freedom’ (Taddja), societal conditioning, and the ‘desecration of sacred nature for human beings’.

Taddja’s performance was seamless – grippingly embodied and physically relentless. This was the director’s vision, to set State of the Ape Address apart from the multitude of other adaptations of Kafka’s short story, one charged with kinetic intensity and emotion.

The emoting fluctuates so much. Initially, I was wrong about it. I read the script and was so angry […] How can we do this as humans? […] But that was Taddja's anger. And so, we had to work to find Red Peter's happy moments, Red Peter's amusement, Red Peter's desperation, Red Peter's fragility, and then emote. (Taddja)

We discussed Taddja’s artistic process of embodiment, the nuances of Kafka’s writing, and the politics of the play’s message and its contemporary relevance, amongst many other things. What stood out to me were some of the misalignments between audience reactions and written reviews around State of the Ape Address and the narrative that Stanley and Taddja told me they were exploring. For example, Taddja told me that during their performance in Mozambique, at the 20th anniversary of the FITI Festival, members of the Portuguese-speaking crowd started walking out. ‘They thought the message was against them’, he told me.

Perhaps what was most interesting was the preconception that the play is about racism. Stanley discussed how common it was for audience members to assume that the capture, conditioning, and identity erasure of Red Peter was emblematic of colonial and neo-colonial practices. A violent epistemic oppression, we agreed, but why did it have to be about race? Was it Malawian Mewzi Arts’ responsibility to tell that story?

People think this play maybe is about racism or maybe it's about slavery […] sometimes we put our focus on the wrong things […] Now, was the reflection to come all this way and really talk about racism? What element of racism are we talking about? I think it would be just trying to force things. (Stanley)

A relevant example is Sam Banda’s review, published in The Times Group from the show’s opening in Lilongwe. Titled ‘State of the Ape Address Touches on Essential Issues’, Banda considered the play’s relevance to ‘pollution, neo-colonialism, modern-day slavery and self-esteem’, centred around the cultural struggles of ‘Black Africans’.

While a compelling and insightful perspective, it wasn’t one confirmed by the cast and crew themselves. I was curious to hear Stanley’s take on the review:

Most audience and reviewers automatically fit the show to [Kafka’s] original’s narrative but I still share that the refreshed objective of [State of the Ape Address] is to encourage or suggest to the audience to apply Red Peter's shared experience on their personal encounters and challenges rather than the broad racial or political cards, which are relevant but not directly as essential as personal situations we drown in […] Those who buy into our refreshed meaning get to see the power and relevance that comes with [the adaptation].

The beauty of Mewzi’s production is the unbounded scope of its meaning. As Taddja illustrated to me, State of the Ape Address doesn’t set out to impart a directed political lesson; instead, it crafts a visceral space of resonance, inviting the audience to confront their own experiences of social oppression and dehumanisation – whatever form those may take. Perhaps it is gendered discrimination – perhaps religion, school bullying, or mental health – like Red Peter, as individuals, we must learn to ‘exist and find a way out of it somehow’ (Stanley). Everyone has their cage.

Read the transcripts below.

Stanley Mambo

So, Stanley, hi!

How are you?

Good thanks. How are you?

Thanks for coming.

Thanks for doing this. This was really good. I'm really glad that I got to see it. Obviously, Kafka's work is very potent; the statements he makes about society and the transformation of man and the fall of man. Why did you choose to put on this play? Were you drawn to a particular thing?

I think it's the whole thing as one unit, in terms of how he goes through the human experience, and maybe the human - the observation of the humanity somehow, though metaphorically, through, through an ape, somehow. So my first encounter with a report to an academy, was when I was an actor in Germany. I think that was 2011. I saw a German version of it, so… which was so interesting. I was drawn to the story. I was drawn to the idea of how we can reflect ourselves through another element somehow. And then as a director, also, I just felt, oh, maybe there's a lot we can do with the piece, and also how it reflected to the universal life - no matter that it was written maybe 1907, and maybe for a specific moment or a specific experience. But taking it out or plugging it out one hundred and maybe twenty something years after, it's still relevant somehow to the modern society. And also, that drew us to say, okay, maybe if we write a fresh thing, it's like we are bringing a fresh story. But my bringing this again, which I reflect as because Kafka was writing more about his experiences, he was not out what I would call a commercial writer, for example. Most of his writing was real. So I think there was something that made him write this production, and I think that things still exists to today; and we felt, okay, maybe it's a bigger statement to bring something from that time, and maybe sure that we are still living in the same than writing something totally fresh.

Yeah, I get that. So, in what ways do you think that this play was majorly different to the one that you saw in Germany?

So, I'm a physical theatre person. So, definitely the one I saw in Germany, and maybe a few that I watched later on YouTube or stuff, they were more pure monologues, I would say. But then with this, I tried to kind of bring out something we are kind of referring to as physical monologue. We tried to explore and seek more of the physicality of the character, maybe, through the emotion, through the memories, he is connecting to - and through his own physicality, also, somehow. And hence the idea even to make it natural - if that can be the word - like no makeup, not try to make him, you know, no elements to add the 'apeness' into him.

Interesting. Why did you choose to make Red Peter go to the military instead of, I think it was a musician in the original?

Yeah, there was just - there's something that strikes me about the military, and then maybe it kind of reflecting that to our day to day lives, you know? So, I saw the militant side of him, which is what I see maybe in many humans - no matter that they are not real military people, somehow. So, it was there with the military stuff and then also I think it inspired the costume design also. Yeah, to get that, but find a different way of bringing through the 'military' and also the executive side of it with the tie.

Yeah, that was a good design.

That was the idea be behind it.

So, you think all humans have a military element?

Yeah, I think for you to move forward, like he said, you know, to keep moving and for you to find your way out, I think there is that militant thing. There is that push you give to yourself, you know, to face the challenges, to face the encounters, or, in some sense, we can say, to fight your wars, you know? Of life. So, that's where we drew that from.

That's interesting. That's really interesting. I guess it contrasted - I don't know, I feel like the original, it was all about music and high society and performance, whereas military is slightly… I mean, it's still a performance, isn't it?

Yeah.

And you were talking about the concept of finding your way out. I feel like that was the most important - the most repeated line in the play was about not having freedom but finding your way out. How do you think that reflects in the state of society that we're in today?

I think - from Kafka's side, I think he was special in in that I think he would serve his ideas and really find what is more essential in every situation. Like sometimes we we seek the wrong things, let's say, in life, yet maybe what we just need is to move forward.

Okay.

So, for example, if we would go into freedom - I think maybe just the word 'freedom' itself maybe has created a lot of chaos in different situations. And maybe in that way, people lack the essential need in every situation. So, I think that what Red Peter needed was to move forward and to find his way out. Because I don't think freedom was a big question in the whole…

Yeah, freedom was a misconception.

Yeah, it was a misconception. And maybe if he dwelled on freedom, or even trying to describe freedom - because he says, I'm deliberating not saying 'freedom' - because it's one way again. Maybe the more we try to define things or even analyse things, you know, we dwell into the wrong things somehow. But I think what is important for him, even for everyone in life, even being in this rich situation, is to move forward or to find your way out, you know? Which is interesting also, because when you think - when he says, 'way out', it is not only to jump out of the box, but to find your way out within the box again. Which is very interesting, because there are many situations we are in as a people or as individuals where maybe the solution is not to jump out, but to find the way out, or the solution within the… but not maybe to stop the machine and cut everything at once.

Yes, it's interesting that you talk about how that we all have to keep moving in the world. I mean, to me, the script - the original and the play - they're both quite sad, because it's reflects on the idea that society push people to fit into a certain category - to fit into a box. Which obviously contrasts the actual box. And therefore, freedom is a misconception, and we have to keep pretending, in a way. But I don't know. What do you think that the message of the play is? Do you think it's sad or not?

I think like so in some of the shows, or some of the venues, or especially when we perform in schools, because we have a program; we call literature alive.

Oh yeah, I heard.

So sometimes we perform for school children and then after the performance we have a Q and A session with them. And most interestingly, I think, which maybe is the original theme of the production, people think this play maybe is about racism or maybe it's about slavery. You know? I would say it's open because it's metaphoric, so it's open. Maybe it depends on what you are seeing in it or what you want to reflect in it. But what I always say, or maybe our idea to bring this show, is just to let everyone or every individual reflect into themselves and how they can find continuity, or how they can continue or find their way out through different encounters they face in life. So sometimes, for example, I give an example that this show should be watched let's say by a young girl child who's growing up maybe in a polygamous family, and maybe there's some religious beliefs that are forcing her to be married at twelve years or at eleven years. And so, is the reflection of this play on slavery going to help her in anything? Maybe it's not. But if she looks at this show and watches it and takes the reflection back to her own life - of this family life and all these systems of culture that she's growing into - and she cannot just jump out of it, but she still has to exist and find a way out of it somehow. So for us, it's from that individual and taking it from them. Because, like we said again in the beginning, sometimes we put our focus on the wrong things. You get what I mean?

I completely get what you mean.

Yeah, like – now, was the reflection to come all this way and really talk about racism? What element of racism are we talking about? I think it would be just trying to force things.

You didn't set up to do that.

Yes, you get it. I think there's more that people can reflect.

That's interesting. I mean, I've asked you so many questions, so thank you so much. That was really interesting to hear your story and your journey with it.

Thank you.

Thank you so much.

Tawonga Taddja Nkonjera

[…]

Stanley was telling me that one of the reasons that he was interested in the show was because of the opportunity for physical monologue and physical theatre. So, I was wondering what was your process in learning or pretending to sound like an ape?

Well, yeah, we had very, very extensive workouts, workshops.

Yeah, I bet!

You know, just exercises, explorations, experiments, you know? And in the beginning, I didn't want to fall into that trap of, say, for example, watching apes or watching videos or movies about something. I didn't want to do that. I wanted to see if, you know - they say we share 98.8% DNA, so maybe somewhere in there I can find it.

You just let it out.

Yeah. The good thing about the director, Stanley, was he always said, give it your all, you know, give it everything. Put everything. Make it like a smorgasbord, you know, so you have a whole lot of things and then we have to take it out if it's too much.

Yeah.

So, it was just a question of release and let go. Yeah.

That's probably quite cathartic.

Yeah, especially, I don't know… there are days where it's really visual and then there are days where the energy is perhaps not there, but each and every time it's an experience.

Yeah, I bet it's an experience.

It's an experience each and every time.

Well, what I was really interested in thinking about before I came to watch the play is: what role do you think that the audience take on? I think that we're quite integral to the production in terms of… If it's a societal piece - that is different for everyone, as we talked about - and it's performed and the audience has to take on a certain role, are we the academy? Or who do you think that we are?

Well, there are moments where, in this show, the way we adapted it, that Red Peter actually addresses the audience. But in the sense of the storytelling, he's within his memories.

Yeah.

Because he thinks in images and in pictures and things like that. So even when he's coming to the academy, he's really already… like he's coming to give the address, but he's more bothered about what the newspapers have written about him. And he's in his mind, and then he realises, oh, these guys are here. Well, I have to address them. But even in addressing them, he's... So, I don't like using techniques or big words in theatre, because I think theatre is as simple as even this connection [between us]. So, I don't want to go into technicalities, but I think the idea of being within Red Peter is more important than telling the audience, hey, listen to my story. So that's why I'm going long winded about the answer.

No, I know, but it makes sense. I understand.

So, yeah, like I said earlier, the audience would perhaps laugh at a moment where you least expect them. And if you are involved with what the audience is doing, it might throw you off track. And this production is mostly about the emotion, like understanding the emotion of literally, literally every single word that you say, you know? And so, if you bother yourself with the audience in the moment where you're supposed to be trapped in the cage, that will take you out. So, my idea is almost to try and never worry about what the audience is doing, whether they like it or not. Let me just be in this moment.

Yeah.

Yeah. We had an experience in Mozambique, in Maputo, at the FITI festival. It was the 20th anniversary of the festival, and we were invited to go perform. So, first, they're predominantly Portuguese-speaking people, right? The English is very minimal, for most of them. Maybe the internationals, they spoke some English. But this is a heavy text and there are particular words that, if you're a Portuguese-speaking, maybe even the meaning of the word just will elude you.

Yeah.

And we had a moment where some people started walking out from the show. And I thought, oh, maybe they're late, or they had some time off. But somebody came up and said, oh, they thought the message was against them. And I thought, oh, I never saw it like that, like that there's a message in here that's directly affecting one particular individual to the point where you're going to walk out of a theatre.

Wow.

Yeah. So, that's why sometimes I think I don't have to worry about the audience; I simply have to worry about the production. We trust our production.

That is seriously lost in translation. Interesting.

Yeah. So, if I worry about the audience, then I will be affected. But yeah…

Yeah. Preach for every actor.

But there are moments where the audience is being addressed as they can. And in that moment, you can't run away from it. He has forced himself to come and really speak. And someone said yesterday that that's when they understood the whole production. It took them time. Fifteen minutes into it, they were saying, where is this going? What's happening? But then when it got to the human encounters, that's when they said, oh, okay, now I'm beginning to get the whole thing.

I agree. I think it was quite important, the breaking of the fourth wall. Because I think that you have that twice in the show, you know? He breaks the fourth wall of his cage, and he breaks the fourth wall of the play. I think that moment for me as an audience member was like, Red Peter wants us to understand him. Which is interesting, because I also thought the line about: 'they don't want to understand, they just want to solve the riddle of my being'.

Yeah, yeah.

And I think to me, that was 100% was my favourite line. What do you think about that one?

Not to be on the side of the humans. Why do we have this fascination about other species? It's not just apes. We keep fish in tanks. We keep dogs in homes. Kittens. Livestock.

There are different reasons. It's power, money, companionship.

But why an ape? For fun? For the circus? For entertainment?

Well, I guess it's the interesting point of the ability of an ape to mimic humans; the dexterity they have. You play the guitar at the end, I thought it was a cool moment.

Yeah. So, we had this discussion where somebody said, do you really think an ape could talk? And instead of answering that question, the question that came to me was, could I learn the language of apes?

Do you think you could learn the language of apes?

I think if you're born into it.

Didn't Jane Goodall do quite well? Yeah, like Tarzan!

I don't know.

Yeah, I mean, it would take a lot of immersion.

Yeah, because you're born into it, right? Like Mowgli. I don't think you could speak the language of foxes or wolves. I don't think you could speak the language of a tiger or a bear or snakes or baboons. But he was existing; he found his own language. I don't think Red Peter knows the difference between leap and jump. That's just me thinking.

What do you mean?

Like, I'm sure he's got a vocabulary that he's learnt in his five years.

Oh, okay.

I don't think he goes into a dictionary or something and says, oh, I really want a synonym for this word. You know? And it's just five years. So, I think his vocabulary is really, really small, considering also that he's not really human. So, when we're saying that Red Peter is talking… I think he said hello, right? And then he said, how are you doing? I want some water, or something like that. Or maybe he said, give me a beer. Whatever. He said something. And then they got excited. Ah, he's talking!

And then they dubbed him a talking ape. The fact that Kafka takes that and then makes a whole, huge short story out of it and then you get to decipher the metaphor of life from that. I think…I mean, it's pre-emptive to try and second guess Kafka, first of all, right? But when you sit down, like for me, every single time I read the script, I'm second guessing myself. I'm wondering, am I… sometimes I even - I don't want to second guess the performance because I believe in the work that we put in; I believe in the rehearsals that we do; I believe in the adaptation artistically. I think that, yeah, we're doing a good job, but of course, it's a performance. You can always get better. And sometimes I do feel like I don't think I was in the right e motion there, you know? But there's nothing I can do about it because in that one hour and five minutes it has to be Red Peter.

Yeah.

So, I think each and every time people see a different show. It can't be really duplicated at that level in terms of technique, but also in terms of emoting. I always have to, for this particular show - I’ve been in so many other productions but, for this particular show, the emoting has to… it fluctuates so much. It fluctuates so much. Initially, I was wrong about it. I read the script and was so angry, you know? The anger that comes with, oh, how can we do this as humans? And that's the anger that I was portraying on stage. And so maybe Red Peter that particular time was more animalistic, more angry about it. But that was Taddja's anger. And so we had to work to find Red Peter's happy moments, Red Peter's amusement, Red Peter's desperation, Red Peter's fragility and then emote.

Interesting. Yeah, that's when I first read it, you get that, anger. But then you read the words that he's saying, ad you just think, this is sort of strange. Why is he speaking like that? He sort of backs humans up sometimes.

Yeah.

That's really weird to watch an audience member.

Yeah, like, I owe everything I've become to the humans.

Do you think that Red Peter is glad that he became a human?

No, I don't think so. I think I really, really, truly believe that if he had any single chance, he would run back to Virunga. Like, a just slight opening. If he could just find it, he would take the way out. He'd take the freedom. That's what he would do. But because he can't, he succumbs, just downgrades himself through the way out. Which is a new way out.

I guess that's sort of one of my last questions is: we were talking about the message of the play - and this production particularly - and whether that is a single one or whether it's malleable for everyone's experience of the world. What drew you to the play and what do you think the message that you're trying to convey is?

So, as far as the adaptation, I think both the director and I, we have this - I don't want to call it, I don't want to, like, seem like I'm putting Kafka on a pedestal or something but - we have this respect for Kafka and we didn't want to, sully the words. So we maintained the text throughout. But to identify Red Peter as our adaptation, and to speak to Malawians - first of all, because the production was first shown to Malawian - to speak to the Malawians, and then to speak to the Africans, and then to speak to everybody in the whole world… we thought something that was written more than one hundred years ago, and if you read it today, it's just as relevant as it's going to be one hundred years later. So why not just tell the story the way it is?

But then, once you read it, you find out that…for me, it's the vanity of everything. You know? That's why in the adaptation, the exclusive words that we added to the text that weren't there: 'desecration of sacred nature for human beings'. When Red Peter, as an ape, is forcing himself to get to the humans so the humans can understand him, but he sees these horns. And the horns now are reflective of human nature, where you shoot a buffalo for the trophy, you know? And perhaps this buffalo used to drink at the same waterhole where Peter drinks, you know? And he knows the smell of this buffalo, and then now he sees it. So, he really tries to fight it and say, help me! Telling the flywhisk, which is an ox tail. Yeah, so it's everything that is in nature, and humans are lording over that nature.

So it's sort of like an element of the corruption of humankind on nature?

Yes. Maybe just not on nature alone. I think it goes beyond nature.

On everything.

We were discussing this, and somebody made reference to Planet of the Apes, and I have to admit, for the first time ever, I've never watched it.

I've never watched it either! I've never watched it either.

I've never watched this movie [laughs]. And everybody who watches this movie, they come back to me and say, oh, Planet of the Apes! Do I actually want to watch it? Because at home people watch it. I've never really…

Yeah, all I know is that CGI is really good.

I've never seen it enough to even make that distinction. So, it's a…but I have watched Mighty Joe Young, which is a movie about a South African actress. And they take her to a concrete jungle. That's the other thing I'm always saying. Even as humans, maybe because we've lost the idea of nature, it's put us in situations where we have to wear a tie, right? And then we have to iron our clothes, yeah. So perhaps we've really created a new nature, and then we've forgotten the old nature. And then maybe capturing Red Peter is our desperate attempt to make ourselves to the old nature, but we still end up completely bottling that. When we were eventually talking with the director, we got to a point where we said, let Red Peter keep the report and let this act of him being required to give a report disgust him. Let it nauseate him to the fullest. But somewhere in there, try and find that little desperation, that little hope that maybe I can appeal to these people, and they can let me go. Just that little hope spring eternal. That's why I said if there was that little hope of leaving, he would.

My last question: I feel like we've kind of talked about the play is being, you know, about humans that are just sort of fucking everything up, which is sort of true. I think that, as you talked about, Peter is forced to give this report. And there's something very human about writing something down and handing it to an academy. And it's sort of this idea of capitalising on epistemologies. And this experience, or this non-human experience. For me, there was also a level that humans are trying to make their point of view the only point of view. They're taking his opinion, and they're going to take it into an academy, and then they're going to twist it into their own story. I don't know if you agree with that. But that's, for me, something that I felt came across: that humans are pushing their own narrative above - and he had that moment of wanting to tell his own. But there's something quite sad about it being formally handed in to an Academy.

I'm enjoying that take. Maybe I do agree with you. (20:11) They have their own agenda. That's why they're reporting this way. Why would you report that? Why would you say his 'apeness' is not yet gone? (20:17) Why are you trying to repress him in the first place? So yeah.

It's like the physical oppression scene with the cage, and how well you do the physical theatre. And that's matched with the epistemic violence within the script. And again, like anything, you can take that to mean whatever you want.

See, now the thing is, every time you discuss Red Peter and his story, I find something new. And now this is going to affect my next performance [laughs]. And then the director will say, we have to rehearse that! Now I have more work. Thanks to you!

Anyway, I've literally asked you guys so many questions.

(Stanley): So, what do you think about the title?

State of the Ape Address? I was thinking about the title, actually, and I was wondering why you chose it.

We had to vote for this production… To be a different production, we made Red Peter from the Virunga mountains in Congo. We made him speak Kinyarwanda, which is the language from the north. And then the director broke down the script into ten scenes that depict the journey of Red Peter. But above everything else, he insisted on this being a physical monologue. So, we had to identify symbolisms and moments that made sense in a physical representation and then people can get their own meanings or find their own interpretation of the message. But then also, we then decided, no, he's going to be a managerial officer. And then he's going to choose to play music.

In terms of the name, the director came up with, was it four different names? I think I voted for a different name. The producer voted for a different name and the director voted for State of the Ape Address. And because he's the director, he became dictatorial about it. I'm not here.

(Stanley): [Laughing] I'm not here. I', not here. I didn't hear that… I didn't hear that!

To be fair, I actually like the title. I don't know what the other options were, but I think the title is powerful because you have that idea of a report, an address. There's something very - the contrast of the concept of an ape talking. And 'address' is very formal. It's something that's very controlled. You know? So, you immediately get that juxtaposition of society and animal.

So, I think following that line of thought, we had a scene - well we actually removed that scene - but when we went to Kenya, in the Kenya International Theatre, Red Peter actually has prepared for this address. And he's got a banner; it was hanging in the presentation room where he's presenting the academy. It says, 'The Conference of Intelligence and Science'. And so, we used to carry that everywhere, it was one of our props. So when Red Peter is coming in, he's going to hang that, to prepare himself for his address. And then he sees, oh, they're already here! And he quickly hangs it up and he starts. But I think the director became more and more minimalistic and said we have to lose that prop.

I think it's an interesting point actually: the concept of being prepared and being science.

Yeah, so maybe he's going to bring it back now. I don't know. But yeah, I think one of the names was Red Peter's Address.

I prefer State of the Ape Address.

The director was right.

Yeah, I think it definitely highlights that it's not really his story. It's a story that's supposed to be written and analysed, if that makes sense.

Red Peter refers to his notes a lot written on the pad. But when he refers to them, he realises: no, I really don't want to talk about this. And he thinks, so what can I talk about? So yeah, there is that apprehension in making his address. So yeah, I get what you're saying.

Yeah. He wants to make it his, but… And he deflects at the beginning: 'no I'm not gonna tell you. Ok, I'm going to tell you'. I thought it was done beautifully.

Thank you so much.

Out of interest, how many countries have you done it in?

Malawi, Tanzania, Kenya, Mozambique, and South Africa.

Wow. So how long have you guys been touring?

Two years now.

Well, it's lucky to have you here.

And actually, your questions are helping us. It's a work in progress. Obviously. So, we're going to watch the video and listen to your questions again, and insights, and see how they can help us build this show.

I'm glad because you gave me a new perspective on it as well. And I think that's what's really wonderful about it, that there are so many ways of seeing it. It almost needs to be watched over and over. But thank you so much for taking the time to answer my questions and speak to me.

No, no, no. No worries.

I'm so grateful.

I appreciate it.

Thank you.

Post a comment